Sightings of Trachemys scripta elegans (Reptilia: Emydidae), a New Potential Aquatic Alien Invasive Species in Trinidad, West Indies

Sightings of Trachemys scripta elegans (Reptilia: Emydidae), a New Potential Aquatic Alien Invasive Species in Trinidad, West Indies

The first sightings of the Red eared pond slider Trachemys scripta elegans in Trinidad were documented by Mohammed et al. (2010). That data included sightings from 2000 to 2010, and anecdotal records from F. Lucas dating back to the late 1980’s (Mohammed et al. 2010). Records from various independent baseline surveys by R.S. Mohammed and S.H.. Ali spanning 2005 to 2016 have now been collated to provide an updated account of the distribution. This species is aggressive, and competes both for food and basking resources with our native wild freshwater turtles (Cadi and Joly 2003) making this a potential aquatic alien invasive species. An Invasive Alien Species refers to a species or subspecies or lower taxon, introduced outside its natural past or present distribution; includes any part, gametes, seeds, eggs, or propagules of such species that might survive and subsequently reproduce; whose introduction and/or spread threatens ecosystems, habitat or species (UNEP, GEF, CABI, 2011).

The natural distribution of T. scripta elegans occurs within the Mississippi Valley, from northern Illinois to south of the Gulf of Mexico (Lever 2003) but this has now expanded to several temperate and tropical regions placing this species in the list of the world’s 100 most invasive species published by the IUCN (Lowe et al. 2000).

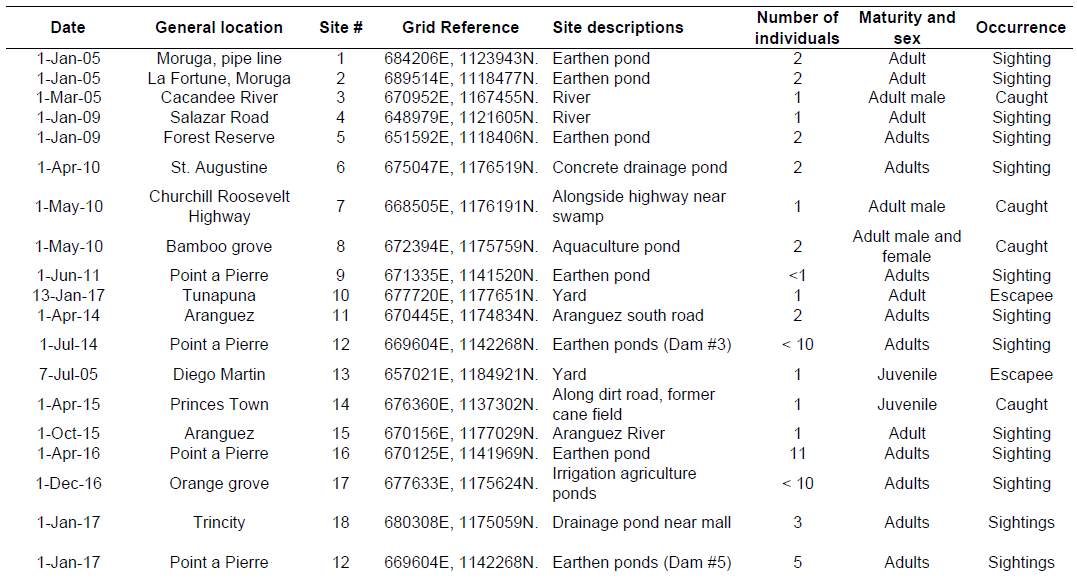

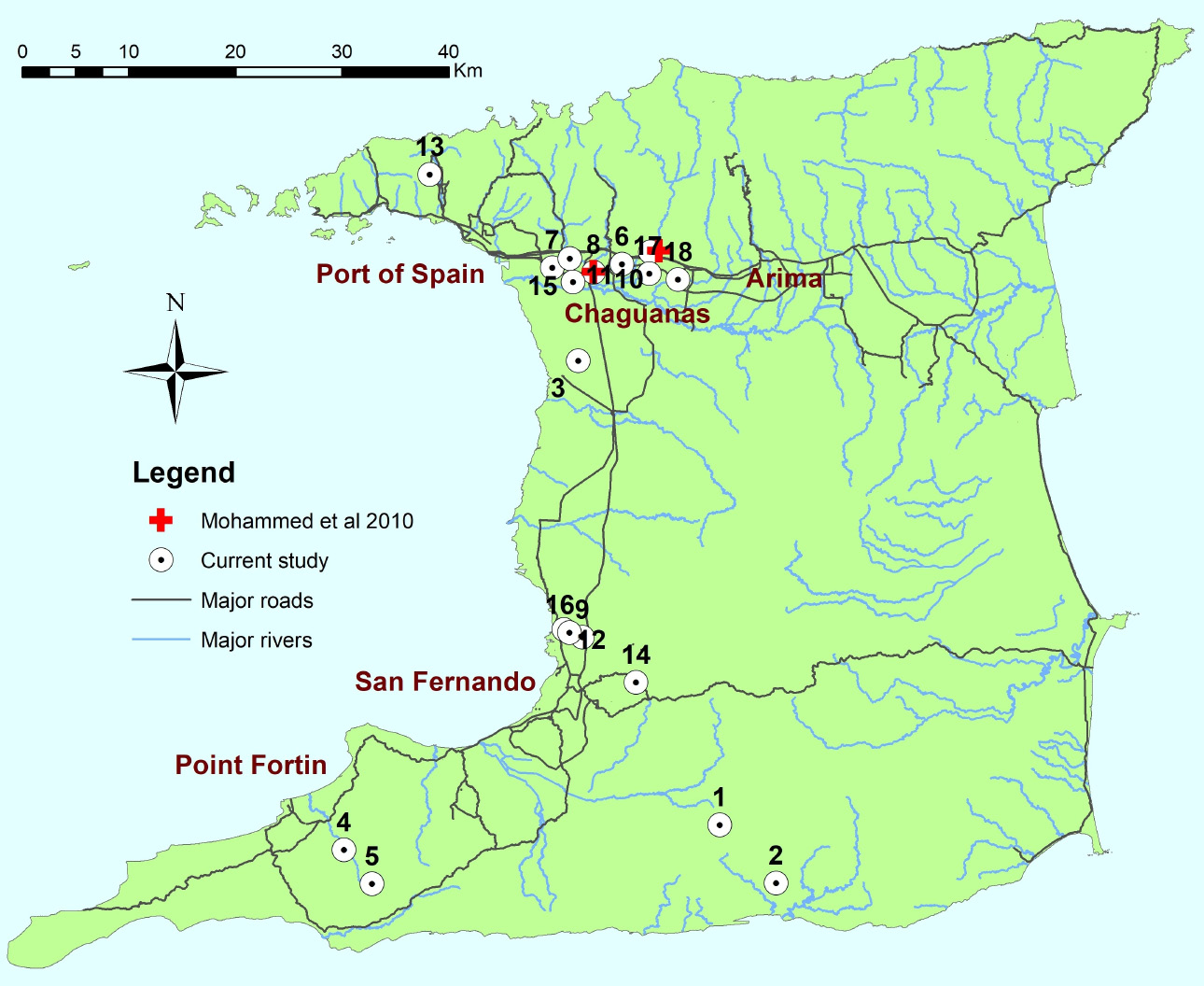

Site records of Trachemys scripta elegans between January 2005 and January 2017 are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1. Notes on escapees and site descriptions where specimens have been caught or observed.

A large majority of these individuals would have made their way to the wild either by escaping from their enclosures or by pet owners’ intentional releasing of animals that they could no longer care for. It is clear the distributions of sightings are very similar to major residential areas which support the suspicion these populations originated from individuals that were released or accidental escapees. Whilst most of the sightings have been of less than ten adults (per occurrence) we assume there are breeding populations as a wide range of sizes are observed but not measured.

Fig.1. Occurrences of Trachemys scripta elegans between 2005 to 2017.

We also suspect the population range might be expanding, however this might be the early phases of the invasion as egg clutches have not been detected. This suspicion is solely on the increased numbers being found at some sites, whereas in the 2010 report (Mohammed et al.) only lone individuals were found. We also suggest there is need to keep an account of the sightings as well as evidence of nesting (eg.egg shells) or juveniles where the density seems high currently. They seem to be ubiquitous as we have noted them in earthen and concrete ponds and rivers with a wide range of riparian and aquatic vegetation types. We have not observed this species being preyed upon by any other animals. They typically live approximately 30 to 40 years in nature (Cleiton and Giuliano-Caetano, 2008).

The authors would like to offer their assistance to owners who feel the need to dispose of their unwanted pets. However it is strongly advised that before pet owners decide to acquire any animal, that they consider the biological and ecological needs of that animal. This would include its dietary requirements, lifespan, territory ranges of the animal and suitable housing as these would reduce the incidences of both escapees as well as intentional releases. The carapace of T. scripta elegans can reach more than 40cm in length, but the average length ranges from 15 to 20 cm (Close and Seigel, 1997) and this should be considered as these are currently sold as juveniles (carapace length <4cm) without any regulation in Trinidad and Tobago.

Lastly, we would like to acknowledge Mr Graham White and Mr Renoir Auguste for informing us of sites where the species were likely to inhabit.

REFERENCES

Cadi A. and Joly P. 2003. Competition for basking places between the endangered European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis galloitalica) and the introduced red-eared turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans). Canadian Journal of Zoology 81: 1392–1398

Cleiton, F. and Giuliano-Caetano, L. 2008. Cytogenetic characterization of two turtle species: Trachemys dorbigni and Trachemys scripta elegans. Caryologia, 61: 253-257.

Close, L.M. and Seigel, R.A., 1997. Differences in body size among populations of red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) subjected to different levels of harvesting. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2: 563-566.

Fifth Draft Strategy and Action Plan For Invasive Alien Species in the Caribbean Region 2011-2015. (UNEP, GIF, CABI, 2011)

Lowe S., Browne M. and Boudjelas S. (2000). 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species. A Selection From the Global Invasive Species Database. IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG), Auckland, New Zealand.

Mohammed, R.S., Mahabir, S.V., Joseph, A.K., Manickchan, S. and Ramjohn, C. 2010. Update of freshwater turtles’ distributions for Trinidad and possible threat of an exotic introduction. Living World, Journal of The Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists’ Club, 2010: 54-58.

Ryan S. Mohammed

Department of Life Sciences, The University of the West Indies.

ryansmohammed@gmail.com,

Kerresha Khan

Department of Life Sciences, The University of the West Indies.

Saiyaad H. Ali

The Serpentarium, Trinidad and Tobago.